Introduction

Welcome to Canadian History, Identity, and Culture. You are about to discover how interactions among Indigenous peoples, French and English settlers, immigrant groups, and the international community have shaped Canada.

Along the way, you’ll analyze major social, economic, and political changes in Canada from early times to the present, and you’ll also analyze how national and international events and responses have contributed to the evolution of national identity and culture.

The course is designed to allow you to interact and participate instead of simply reading the material and absorbing the information. So the more you engage, the better!

Questions you may explore include:

- How has the mix of cultures influenced the development of Canadian society?

- Which modern issues have roots in Canadian history?

- Which factors have had the most impact on the formation of Canadian identity: immigration policies, democratic values, colonization, or Indigenous peoples?

- Do European thinking, history, and culture dominate Canadian history?

- Which pivotal turning points in history have shaped Canada’s identity?

- Does Canada have an identifiable status or image in the world? How has it evolved?

- Has Canada learned how to represent all cultural, linguistic, ethnic, and other groups in its society with equity?

- How have politics, social changes, the arts, economics, and technology influenced the development of a Canadian identity?

Give these questions some thought now, and you’ll come back to them at the end of the course. By examining some of the big questions surrounding Canadian history, you’ll develop a broader understanding of what “Canadian identity” means.

Learning notes

Periods of Canadian history to be surveyed include:

- Indigenous communities and life pre-contact

- Colonial Canada

- The Dominion of Canada

- Modern Canada and Indigenous Rights

In each period you’ll examine significant social, economic, and political events, as well as the people and organizations that affected the development of history, identity, and culture in Canada.

Pre-contact is your starting point.

Pre-contact is the period before Indigenous people met European settlers. During this time, Indigenous lands were not occupied by any foreign, colonial governments. Rather, Indigenous peoples had particular connections and histories tied to particular places which impacted the way that they lived and how would come to understand the world around them. From languages to traditions to the stories communities told, geography helped form specific community worldviews.

Since contact with European settlers happened at different times with different Indigenous communities , there is no specific date to assign to contact. Contact happened (and pre-contact ended) over time as Europeans settled on Indigenous lands.

What was community, family and governance like for Indigenous peoples before European contact? In this learning activity, you’ll learn about this.

You’ll be introduced to some concepts you can use to analyze historical events – the historical thinking concepts – and to the process of inquiry. You’ll use these analytical tools in this course. You’ll begin with examining some of the aspects of Indigenous community life prior to contact with Europeans.

Before European Contact

What you will learn

After completing this learning activity, you will be able to

- describe what First Nations societies were like, how life was organized prior to European contact, and also describe aspects of those societies’ spirituality, oral traditions, political and economic organization, and arts and culture

- use appropriate terminology when communicating about topics

- identify four big historical thinking concepts you’ll work with in this course

- explain the historical inquiry process you’ll use and see how it may apply to everyday life

- differentiate between the types of historical sources you’ll use

- analyze the credibility of historical sources

Pre-contact traditional territories

For some, it may be difficult to visualize what Canada might have resembled without provincial borders or the population that inhabits it now. This was when the country, you now know as Canada, was made up of traditional territories. These traditional territories comprised Turtle Island.

Let’s learn a little bit more about the concept of Turtle Island.

Turtle Island is the name many First Nations people and communities use to refer to lands known as North America today. In many First Nations creation stories, there are references to a human world that is flooded by water. The turtle is featured in various versions of these creation stories and is an integral part to providing land and life to first people on Earth.

Traditional territories are the places that Inuit and First Nations peoples occupied before contact with Europeans. Métis peoples were born of the relationships between European and First Nations people, and thus we call their history before contact, pre-Métis history. These territories reach across Canada and were the places where people hunted, fished, and raised their families. These lands have deep significance to Indigenous peoples.

Instead of formal borders, Inuit and First Nations peoples had areas that they settled in but weren’t formally restricted to. Borders, like the border that separates Canada from the United States today, didn’t exist at the time. Nations did fight, and war was a part of pre-contact society, as food shortages and land disputes sparked wars between nations. However, treaties or agreements were made to end the violence and to continue living peacefully but separately on the land. In some cases, nations even came together to live as one. Like any event in history, pre-contact events cannot be oversimplified: specific events unfolded with unique circumstances and resulted in very specific outcomes.

Indigenous peoples are distinct groups with diverse traditions, territories, cultures, and communities. First Nations and Inuit groups had their own forms of government, community and family structures, knowledges, teachings, traditions, and ways of knowing and understanding the world around them.

Decision-making processes

How early Indigenous communities lived and were governed is explained in an ebook from the aadnc-aandc.gc.ca (now Indigenous and Northern Affairs Canada), titled “First Nations in Canada.” You’ll read part of the first section on “Early First Nations: The six main geographical groups.”

Press Early First Nations: The six main geographical groups (Opens in new window) to access this eBook section.

Notebook

When you encounter a notebook section like this one, you will be invited to answer questions from the learning activity. Setting up a notebook can be helpful to record your answers.

Your notebook can be a paper or digital document. You may also use your notebook to record notes and ideas from the learning activity.

Explore your first notebook questions now.

- How were decision-making systems similar and different among the Plains First

Nations, the Pacific Coast First Nations, and the Inuit?

Similarities: Among the Plains Nations and Inuit, skills qualified you for leadership.

Differences: The Pacific Coast Peoples had a more structured social system. The leaders were nobles and they made the decisions. It seems like more of a monarchy and less of a democracy than the systems used by Inuit and Plains peoples.

-

Indigenous communities had systems of local governments but no overriding central

government. What are the advantages of this type of government system? What are the

disadvantages?

Advantages: Independence and autonomy. Local governments can act more quickly if they don’t need other groups to agree with their decisions.

Disadvantages: With no central decision-making body, efforts to deal with the incoming Europeans were not co-ordinated. One nation may not have known what others are doing, so there could be conflict and confusion among them.

Terminology

As you've read about in the eBook, Indigenous peoples had vibrant communities. They had their own forms of governance, science, inventions, knowledges, social structures and spirituality. Most were quite nomadic, getting food from hunting and gathering. Some, like the Haudenosaunee and Wendat, were agricultural and, therefore, settled in one place for a longer time.

It is respectful to use appropriate terminology when talking about First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples, their histories, communities and nations.

As you move through the course, the correct language will become familiar. However, as you get started, you may wonder which terms are correct.

For your reference, the University of British Columbia provides some definitions on the website for its Indigenous Foundations program: “Indigenous Foundations terminology (Opens in new window).” You can refer to that document now or whenever you’re in doubt.

Language used in this course

Additionally, for a few notes on how terms related to Indigenous peoples, names, and history will be used in this course, see the reference document “Notes on language and terms (Opens in new window).”

In the next part of the learning activity, you’ll get an overview of some of the tools and processes you’ll use throughout the course – your historian’s toolkit. Your study of life and culture in Canada in the early days will continue in Learning Activity 1.2.

Historical thinking concepts

When you’re studying history, how do you differentiate between all that happened in the past and what becomes history?

According to University of Toronto historian Ruth Sandwell:

While the past is every single thing that happened or was thought about or dreamt of – every event, thought, belief, atom moving, tree falling in the forest while no one was there – history, on the other hand, is someone’s attempt to bring order and meaning to that chaos of everything-ness.”

Source: Sandwell, R. (2003). Reading beyond bias: Using historical documents in the secondary classroom. La Revue Des Sciences de l’éducation de McGill, 38, 168–186.

In studying history, you’ll learn facts about people, places, and events, but more importantly you’ll learn some ways to think about history. These are known as historical thinking concepts. There are 4 Concepts of Historical Thinking:

- Historical Significance

- Cause and Consequence

- Continuity and Change

- Historical Perspective

Historical thinking concepts are like guide posts that help you “think historically” so you ask and answer questions that focus on what is significant.

You’ll be using four historical thinking concepts during this course. Access the following tabs for a brief introduction to each of them.

Why use historical thinking concepts?

Historical thinking concepts will open up your study of history. They put the focus on relevant questions, and you’ll be able to form your own opinions and assess the claims of others based on evidence. Each concept gives you a different lens with which to view and filter information, allowing you to see the evidence in a new light.

When you apply historical thinking concepts to real events, you become more actively engaged in the study, practice, and interpretation of history. The research, analysis, interpretation, and presentation skills you gain through this approach will become tools you can extend, develop, and use in all areas of study and in other aspects of your life.

After you create an effective question using historical thinking concepts, the next step is to gather and organize information to answer it. This involves sifting through information.

Tools for inquiry

In all areas of study, the inquiry process is important because it helps you determine how to find the best kind of sources for any topic that interests you. Being able to conduct effective inquiries and develop relevant responses is part of being information literate. Information literacy is important because you need to be able to filter all the information you have available and separate what’s true, useful, and accurate from that which may lead you to incorrect conclusions.

The inquiry process

Inquiry is a multi-step process used to formulate questions, gather, organize, and analyze information, evaluate and draw conclusions, and communicate results. Although the stages are not always done in the same order, this graphic from the Ontario Ministry of Education provides a summary of these steps. Examine the diagram to see how the steps relate.

Notice that the stages are not linear; however, often the starting point for many inquiries is with the formulation of a question. Once your question has been identified, the process continues through the other stages.

Developing questions

It’s important to be able to develop effective inquiry questions. You want to develop questions that are open-ended; that is, questions for which there is not just one right answer. Why? The purpose of inquiry is to add new knowledge or insight to the topic. There is not much value in focusing on a question that’s been thoroughly answered before you start.

How do you know a question is effective?

Some criteria for effective inquiry questions are given in IQ: A Practical Guide to Inquiry-Based Learning, by Watt and Colyer, as seen in this excerpt:

Source: Colyer, J., & Watt, J. G. (2014). IQ: A Practical Guide to Inquiry-Based Learning. Oxford University Press.

- A good question is an invitation to think (not recall or summarize).

- A good question comes from genuine curiosity and confusion about the world.

- A good question makes you think about something in a way you never considered before.

- A good question invites both deep thinking and deep feelings.

- A good question leads to more good questions.

- A good question asks you to think critically, creatively, ethically, productively, and reflectively about essential ideas in a discipline.

What is a good inquiry question?

McMaster University asked some of the teachers and professors who teach inquiry to describe a good inquiry question. Here is an excerpt from their website that lists some of the responses they received:

Source: Roy, D., Kustra, E., & Borin, P. (2003). What is a "Good" Inquiry question? McMaster University. https://cll.mcmaster.ca/resources/misc/good_inquiry_question.html

- Most importantly … something you are interested in.

- The question is open to research. This means you should be able to find some answers to the question by doing research….

- You don’t already know the answer, or have not already decided on the answer before doing the research.

- Too often, we go after questions for which we already have some kind of answer.

- This might make it easier to write a quick paper but really violates the spirit of genuine inquiry.

- The question may have multiple possible answers when initially asked.

- The question should not be answered by a simple yes/no.

- Questions that examine “why” rather than “what” can help. “What” tends to lead to descriptions or single right answers. “Why” tends to lead to explanations.

- It has a clear focus.

- Some focus is required to allow productive research…

- Your final question should be as direct and specific as possible, or have clear sub-questions. This will give you a good starting point …

- The question should be reasonable.

- This means that there should be credible information which you can use to research your question. …

- Having the right answer matters to you.

- This may seem an odd thing to include but it is at the foundation of inquiry.

- Inquiry is about needing to know the answer to a question, or researching a question where the answer has consequences, so there is some pressure to get it right. Anything short of this can be a game, fun, mentally stimulating, but isn’t genuine inquiry.

Notebook

Use your notebook to respond to the following questions.

To get some practice in choosing and creating effective questions for inquiry, examine the following examples. Using the list of suggestions you have just examined, which of these could make a good inquiry question, and which are not so effective? Explain your decisions.

- Who was the first prime minister of Canada?

This is not a good question for inquiry because it can be answered in a few words with known facts. It’s a closed question, so additional work may not reveal any new information or insight. A more effective question might be “Why was Sir John A. Macdonald elected as prime minister in 1867?” This allows you to express an opinion and to try to prove it.

- Who was the best (or worst) prime minister of Canada?

This is a better question for inquiry because there is more than one possible answer. You could find evidence to make an argument in support of a number of different answers. Although this question is not very original and has probably been studied before your inquiry, evidence and interpretation may add some new information, insight, or a new point of view.

- How should Canada today address historical wrongs done to

Indigenous Peoples?

This is a better question for inquiry because there is more than one possible answer. It could be improved by being more specific about the people to be studied and by indicating a time frame. That could lead the researcher toward new insights into the alliances that were formed at a specific time.

- How have government relations with Indigenous Peoples affected

Canada and Canadian identity?

This is a less effective inquiry question because it only requires listing examples and does not involve making a judgement or drawing a conclusion.

An inquiry process is used in most subject areas and even in most business contexts. Following the process helps ensure you are asking meaningful questions and using appropriate sources to find the evidence and answers you need.

Historical sources

Sources and evidence

After you formulate a good question, a logical next step in the inquiry is to gather and organize information, sifting through it to find evidence. Some instructions on how to do this and what questions to ask are provided in the accompanying video.

The short video you’ll view was developed by a well-respected educational organization called the Critical Thinking Consortium. They’ve produced a number of short videos to introduce historical thinking concepts.

The one you’ll view now discusses the idea of evidence and interpretation. It provides a brief overview on how to gather and assess evidence and sources, and what questions to ask.

Note: The example used in the video relates to a period in the nineteenth century, but it provides an overview and examples of evidence that are useful in any historical period.

To summarize, as Peter Seixas and Tom Morton explain in The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts:

Evidence is what is left behind over time. You may find traces of what happened in the past in historical documents and objects that have been preserved. Evidence is developed through a process like this:

Source: Seixas, P., & Morton, T. (2013). The Big Six Historical Thinking Concepts. Nelson Education. Oral Traditions. (n.d.). Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/oral_traditions/

Press here for a long description.(Opens in newwindow)

When you begin to research a specific topic in this course, you need to know that there are two main types of sources that you will be using.

Primary sources

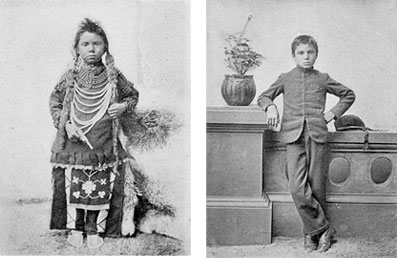

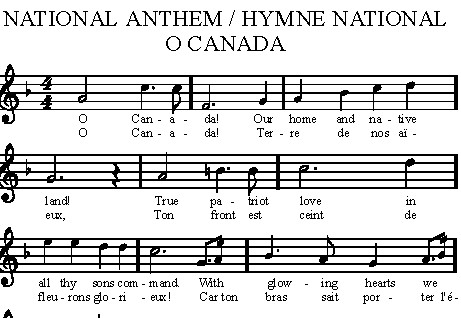

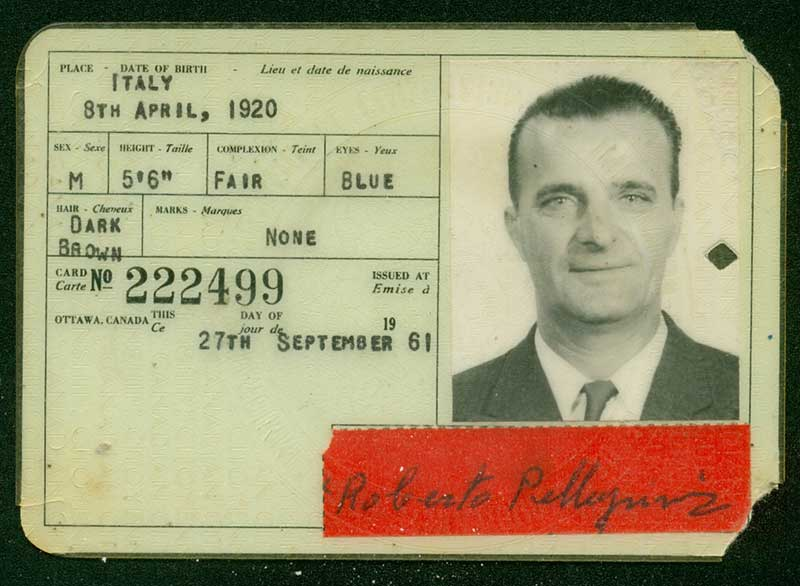

Primary sources are materials that are original in nature such as pieces of evidence in the form of documents, diaries, autobiographies, film footage, photographs, letters, etc… that were produced at the time of that historical event.

Any item leftover from the past can be considered a historical source. It could be a document, but it might also be an object, a photograph, a building, a piece of art, a piece of clothing, or even a fragment of music. These are all sources because they all provide information that can add to an understanding of the past. As you saw in the video, historians usually want to use evidence found in primary sources in order to develop their own interpretations and conclusions.

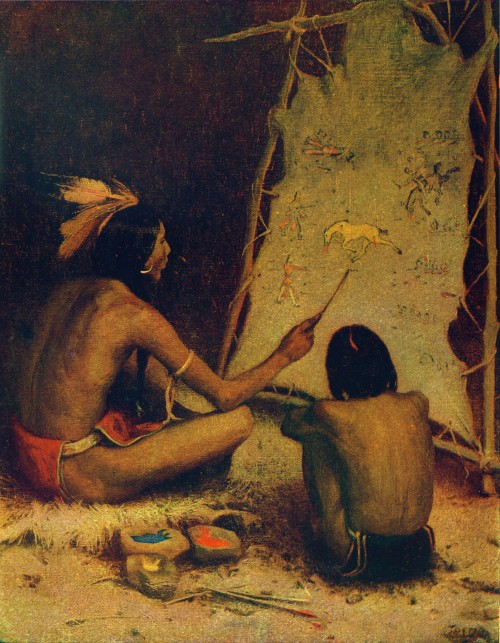

Sources become historical evidence when they are used to develop a sense of the past. For example, the following images show various types of historical sources. The evidence they provide depends on what you are inquiring about.

Oral history

Another type of evidence from the past is oral (or spoken) history. Oral histories are gathered by talking to people about their experiences, families, and so on, or from reading or listening to these accounts.

The history of Indigenous Peoples in Canada has mostly been kept as oral history passed down by Elders through storytelling.

The Historian – An Indigenous artist paints in symbolic language on buckskin to explain the story of a battle with American soldiers.

In this excerpt from “Oral Traditions” in the University of British Columbia’s Indigenous Foundations program, you’ll learn that oral histories have not always been valued by Western European historians:

Western discourse has come to prioritize the written word as the dominant form of record keeping and until recently, Westerners have generally considered oral societies to be peoples without history. This could not be further from the truth. Oral societies record and document their histories in complex and sophisticated ways, including performative practices such as dancing and drumming. Although most oral societies, Aboriginal or otherwise, have now adopted the written word as a tool for documentation, expression and communication, many still depend on oral traditions and greatly value the oral transmission of knowledge as an intrinsic aspect of their cultures and societies."

Source: Oral Traditions. (n.d.). Indigenous Foundations. https://indigenousfoundations.arts.ubc.ca/oral_traditions/

Secondary sources

Secondary sources are developed when a historian uses primary sources to write about a topic or to support a position. Secondary sources are written from the author’s perspective of a historical event, although they may contain pictures, quotes or pieces of the primary sources being analyzed.

One example of a secondary source is a history textbook. If you had a textbook for this course, you could consider it a secondary source. This course is also a kind of secondary source because it uses pictures, quotes, and other primary sources, but also offers comments and provides a perspective on these primary sources as they are presented and explained.

Secondary sources can be very helpful to support your own thoughts or opinions on other historical sources. For example, if you say you believe something about a recording of Indigenous music and you can back that up with another author’s opinion that agrees with yours, it strengthens your argument.

Assessing sources and evidence

Information you use in historical inquiries may come from traces of the past or from historical accounts.

Traces are bits and pieces of the past that may provide clues about an event, person, or time period. As you saw in the previous examples, traces are often primary sources, such as photos, maps, tickets, signs, or letters.

An account, on the other hand, is a description or explanation that “accounts for” an event. It could be a primary source of information, such as an audio recording, an eyewitness report, or a trial transcript. It may also be given in a secondary source, such as a history textbook or a documentary film.

When you choose evidence, make sure it is valid and accurate. The validity of the evidence depends on its source and its use. You need to ask these questions: What is the bias of the author/creator of the source? How accurate and complete is the evidence (is something missing?) What was the purpose of this source? In what context was it created and how do you know?

Making judgements

There are four main concepts to keep in mind when selecting historical sources (or sources for any other course):

Examining for sources

You’ll find plenty of secondary sources through databases, the Web, and in libraries. To use a primary source, you may need to visit a reference library, a museum, or archives. If you are lucky, you may be able to collect primary-source information from the sources themselves!

Here is a list of some of the more common places to examine.

Databases

Searching a database of scholarly articles will provide you with material that is more reputable and well written than doing a basic search on the Internet. Using a database such as Google Scholar can help you find articles written by people who know what they are writing about.

Articles on the Internet

When you find an article online that deals with your topic, search for background biographical information about the author. This could be at the top or the bottom of the article. It is a good way to tell if the author is a reliable, trustworthy source.

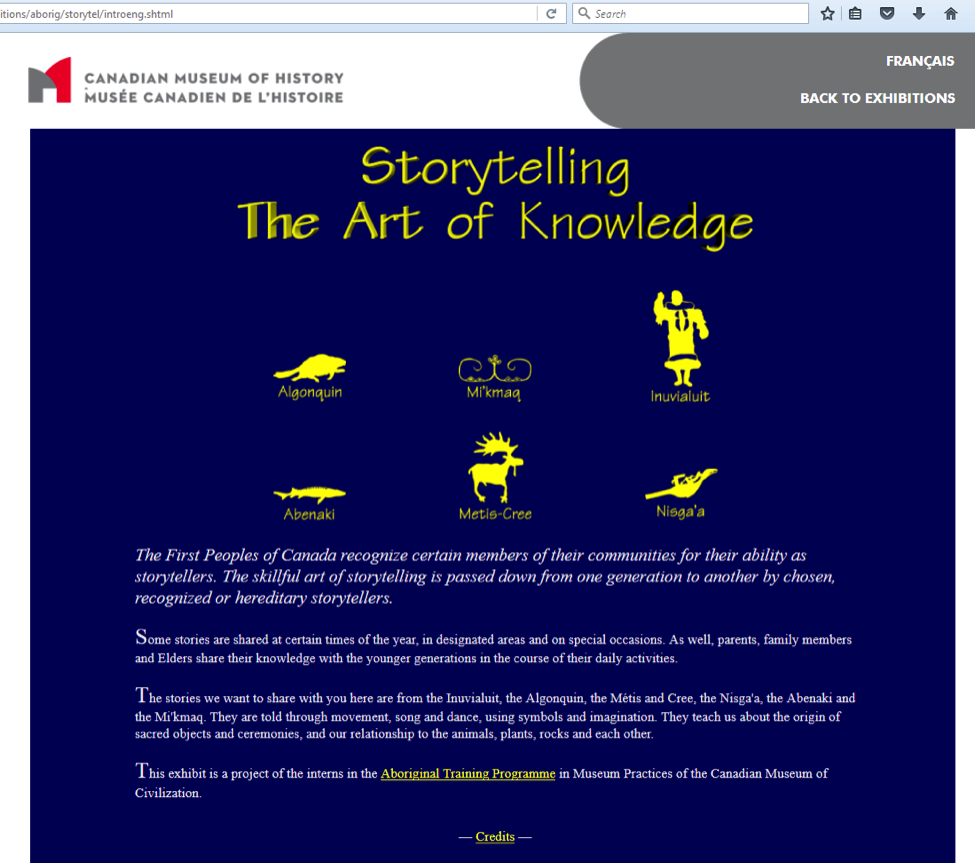

Here is an example of a web page. It has no author, but a few key details tell you that it is a reputable and reliable source. Examine and try to identify these details.

Press here for a long description.(Opens in newwindow)

The web page shown above is on the website of the Canadian Museum of History. If you search online for this organization, you will discover that it is a government-run museum with a database set up for Canadian citizens to explore history.

In the section “About the Museum” on their website, they quote their mandate from the Canadian Museum of History Act:

To enhance Canadians’ knowledge, understanding and appreciation of events, experiences, people and objects that reflect and have shaped Canada’s history and identity, and also to enhance their awareness of world history and cultures.

Source: About. (n.d.). Canadian Museum of History. https://www.historymuseum.ca/about/

Wikipedia

Wikipedia is a free online encyclopedia that is constantly updated and improved by users. Many people start their online research with Wikipedia. It’s the first website many people consult when they want to quickly familiarize themselves with a topic.

It’s acceptable as a starting place for your research. You can use it to check facts, or to find “leads.” It can be a springboard to more in-depth research because articles are usually supported with references or links to the sources.

For an academic historical research paper, however, Wikipedia is not acceptable as the main source. You may start your research there, but be sure to track down credible primary and secondary sources if you plan to use the information in your own work.

Keep in mind that Wikipedia is a shared resource that many people create, edit, and add to. The information is reviewed and errors are corrected, but it’s not 100 percent reliable at all times. Make sure you check other sources to verify that information is correct.

Note that some elements in Wikipedia are perfectly acceptable in academic papers and essays. For example, Wikipedia and Wikimedia images are often well documented, copyright free, or shareable. Just exercise judgement.

Context

Context refers to the setting for an idea. Background information is sometimes needed to fully understand what an article is about. You may have heard someone say, “Don’t take that out of context.” This means you should not misinterpret what is written or said by not including enough background facts.

Sometimes if you are doing research and you find an article about your subject, you might be tempted to take small amounts of information from the source, even one or two sentences, and simply move on. This may cause you to take the information out of context. Be sure to take some time to read or listen so that you understand the context.

Citing sources

Whenever you are citing sources that are not your own in this course, you’ll use the citation style as indicated in the Chicago Manual of Style.

For example, the information you read from the website called firstpeoplesofcanada.com would be documented in a specific citation style. In Chicago Manual style, the citation would appear like this:

Accessed November 12, 2015. http://firstpeoplesofcanada.com/fp_groups/fp_groups_overview.html

Pay attention to the types of information recorded, the order it’s in, as well as the punctuation and capitalization conventions. All of these details are important when using a specific citation style.

For more information on how to use the Chicago Manual style, refer to the “Chicago Documentation Style Guide (Opens in new window).”

Conclusion

In this learning activity, you were introduced to pre-contact life in Canada. You also had a preview of some of the tools and processes you will be using in the course, including the inquiry process, historical thinking concepts, and primary and secondary sources of evidence.

In the next learning activity, you’ll learn more about Indigenous nations and communities pre-contact and explore some of their experiences with colonization. As you learn about this turning point in history, you’ll begin to use the tools of historians.