Learning Goals

You are learning to:

- explore what it means to be a critical thinker.

- start to develop good questions and learn about political inquiry that they will use throughout the course.

- follow the steps in a political inquiry process and begin to use it to investigate First Nations, Métis, and Inuit challenges.

- formulate increasingly effective questions to guide their explorations of themes, ideas, and issues related to First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives.

- connect problem-solving to social action and begin to move from a place of questioning to place of action.

Success Criteria

I am able to:

- make connections to my own relationships with the world around me and how this forms my worldview and decision-making.

- start to apply the four political thinking concepts.

- dig deeper into my understandings of political inquiry through the inquiry process.

- make connections to critical thinking, political inquiry and social action.

- reflect on my skills and strategies and set goals for myself in the course.

Relationships

In this unit, you will learn about the foundations of how First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities had, and continue to have, relationships with the world around them. Through political inquiry and critical thinking, you will examine the ways in which Indigenous Peoples traditionally had relationships with the Earth and how this informed their identities, roles and responsibilities, governance structures, and more. You will learn how these relationships were the foundations for the original intentions with settler communities and connect your understandings back to your lived experiences and local communities.

In this learning activity, you will first explore how you form relationships with the world around you. Like much of the content in this course, you will be asked to explore the guiding question and connect what you learn about First Nations, Inuit, and Métis Peoples to your own understandings of the world including your social and political views, decision-making, and what problems you hope to change in the world.

In the course overview, you were introduced to the framework around how First Nations, Métis, and Inuit related to themselves, each other, and the world around them.

Relationships around me

Take some time to examine the model of First Nations, Métis, and Inuit relationships more deeply and start to think about how you create relationships with the world around you. How does your identity (language, geography, location, ancestors, family, traditions, community, and so on) impact you, your ideas, and actions in the world?

Consider that the term "family" has evolved in so many ways over the years. For some, it is a large part of everyday life while for others, it may be something to continually question and define. The term is on a continuum of sorts and one thing is for sure, "families" change.

The term itself is not without controversy because of a non-exact definition and that means it is open to interpretation. What constitutes your idea of "family" should be decided by you.

It is important to note that every family is unique in their own way.

Portfolio

Brainstorm a list for yourself to begin to try and answer the following questions and add your thoughts to the print or digital folder that you are using for portfolio entries.

- How do I form relationships between myself, others, and the world around me?

- How do these relationships impact my identity, ideas, and actions in the world?

Create a mind-map or image similar to the framework for First Nations, Métis, and Inuit relationship with the world to track your ideas. Use shapes, colours, and other details to differentiate between the criteria as demonstrated in the illustration framework. You can also use arrows to show how you "move" between these elements; for example, maybe your identity forms the centre shape and then surrounding "you" are arrows to and from the elements that influence your identity (language, geography, location, ancestors, family, traditions, community, and so on).

What does it mean to be a critical thinker?

Part of how we form relationships with the world is also based on how we think about and question what happens in society. Our worldview informs what we believe, what we value, and how we act or behave. In this course, you will develop yourself as a critical thinker and an active citizen through the inquiry process.

What is the inquiry process?

To explore this course and First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives, issues, and experiences, you’ll use the inquiry process. You’ll be using this process to investigate events, developments, and issues; find solutions to problems; reach supportable conclusions; and develop plans of action.

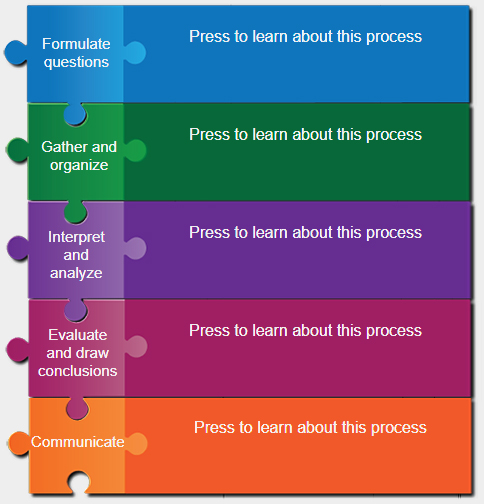

The inquiry process has five basic components. You usually begin the process by formulating questions. Although the following interactive diagram outlines the process step-by-step, you won’t always follow these steps in this order. For example, you can do the following:

- start with a question, and then gather and analyze information and evidence to investigate it

- start with evidence and analyze it to draw conclusions, and then ask questions to clarify your findings using the other steps

- use the entire process

Access the following interactive entitled Inquiry Process to learn about it.

Press here for the accessible version of Inquiry Process. (Opens in a new window)

Press the Start button to access the following interactive. This interactive will open in a new window, press each coloured puzzle piece to learn more about each step.

Start (Opens in a new window)

Start (Opens in a new window)

When you do an inquiry using this process, you’ll find that it will not always result in one "right answer."

In order to evaluate your effectiveness as your inquiry proceeds, you’ll need to pause and reflect after each step, as you may need to adjust your process before continuing. For example:

- When you formulate questions, check that they are relevant before moving on to the next step.

- When you gather and organize information, check that your evidence is accurate.

- When you interpret your evidence, verify the logic of your analysis.

- When you begin to form conclusions, ensure that you can support them with strong evidence.

- You will be communicating throughout the inquiry process, when formulating questions, organizing and analysing information, and critically evaluating your findings.

Political thinking concepts

In the previous learning activity, you were briefly introduced to political thinking concepts. As you use the inquiry process, you will also use four concepts of political thinking as guides, to help you focus on relevant questions. The four political thinking concepts are: political significance, objectives and results, stability and change, and political perspective.

Each concept gives you a different lens through which to perceive and filter your information, allowing you to understand issues and evidence in a number of different lights.

Explore the following interactive to learn more about Political Thinking Concepts.

Press here for the accessible version of Political Thinking Concepts. (Opens in a new window)

Press the Start button to access the following interactive. This interactive will open in a new window.

Start (Opens in a new window)

Start (Opens in a new window)

Summary: political thinking concepts

Access the following Political Thinking Concepts (Opens in a new window) summary document to download and/or print as a reference.

| Political significance | Objectives and results |

|---|---|

|

I can use the concept of POLITICAL SIGNIFICANCE, through the inquiry process, to:

|

I can use the concept of OBJECTIVES AND RESULTS, through the inquiry process, to:

|

| Stability and change | Political perspective |

|

I can use the concept of STABILITY AND CHANGE, through the inquiry process, to:

|

I can use the concept of POLITICAL PERSPECTIVE, through the inquiry process, to:

|

Source:

Learning Resources (Political Thinking Poster). (n.d.). Ontario History and Social Science Teachers’ Association – Association Des Enseigant.Es Des Sciences Humaines de l’Ontario. Retrieved October 7, 2021, from https://ohassta-aesho.education/learning-resources/

Take a break!

Excellent work! You have just completed the section on political thinking concepts. Now is a great time to take a break before you move on to the next section on Examining the inquiry process.

Examining the inquiry process

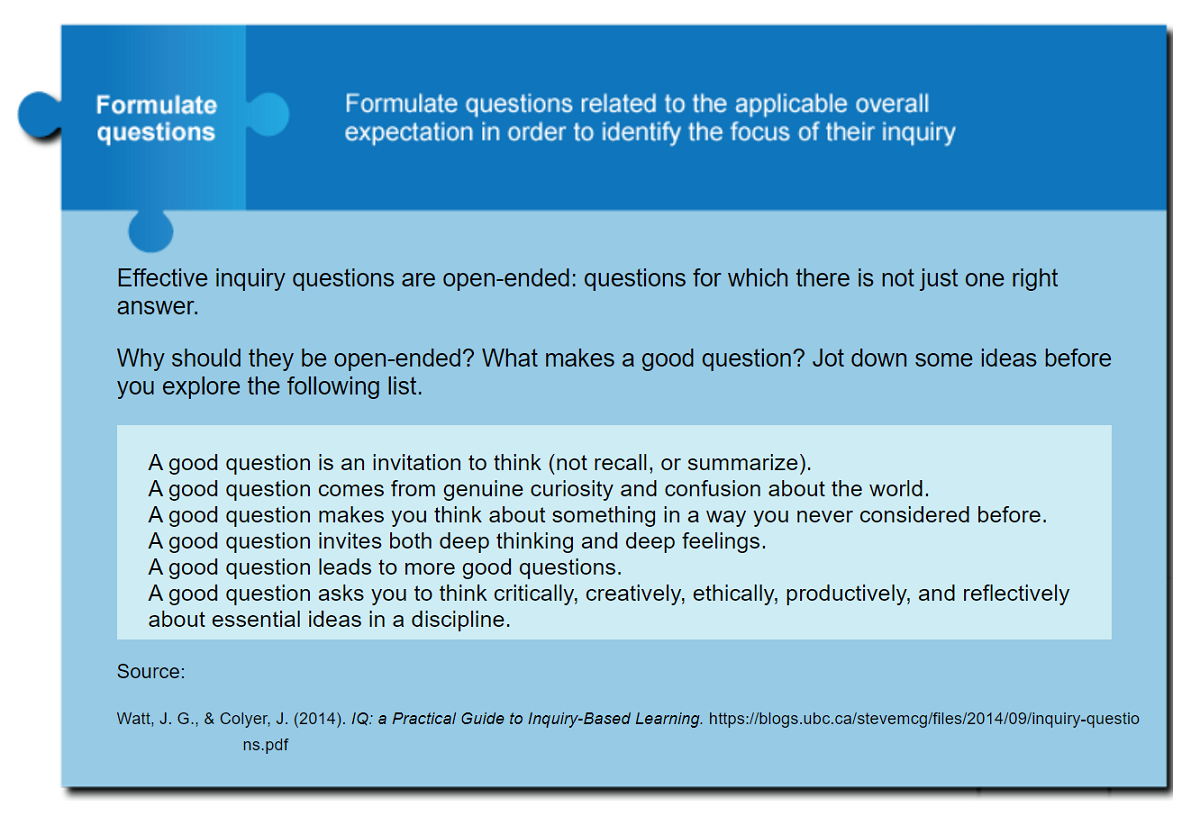

The political inquiry process can help you explore a topic you are interested in, making it easier for you to have an impact when you become actively involved in an issue. To become better acquainted with the process, review the following steps in more detail. The initial step is formulating effective open-ended questions as shown in the following image.

Examples of inquiry questions

The following are some examples of good inquiry questions:

- Why is it important to learn about First Nations, Métis, and Inuit perspectives?

- What does it mean to be an active citizen?

- How should the government work?

- How should one balance individual rights and the common good?

- How should human rights be protected and ensured for all?

With questions like these, there isn’t just one answer. You have to work to find your own. That process builds skills and abilities.

Choosing and creating an inquiry question

To get some practice in choosing and creating effective questions for inquiry, attempt the following notebook activity.

Notebook

Answer the following questions in your notebook, and comment on the effectiveness of each one as an inquiry question in your responses. Rewrite any questions that you think need improvement and turn them into effective inquiry questions. You may compare your answers to the student examples to check your understanding.

-

Who was the first Prime Minister of Canada?

Student answer: This is not a good question for inquiry because it can be answered in a few words, with known facts. It’s a closed question, so additional work may not turn up any new information or insight. A more effective question might be, "Do you think that Sir John A. Macdonald was a good Prime Minister?" This allows you to express an opinion and try to support it.

- Who do you think was the best (or worst) Prime Minister of Canada? Support your opinion with evidence.

Student answer: This is a better question for inquiry because there is more than one possible answer. You could find evidence to make an argument in support of a number of different answers. Although this question is not very original and has probably been studied before, your inquiry, evidence, and interpretation may add some new information, new insight, or a new perspective.

- How should Canada address its historical injustices towards Indigenous peoples?

Student answer: This question meets the criteria for a good inquiry question because there is more than one possible answer. It requires research to find evidence to support a position.

- What government decisions have affected First Nations, Métis, and Inuit peoples and their identities?

Student answer: This is a less effective research question because it only requires you to list examples and not make a judgement.

An inquiry process is used in most subject areas. Following the process helps ensure that you’re asking meaningful questions and using appropriate sources to find the evidence and answers you need.

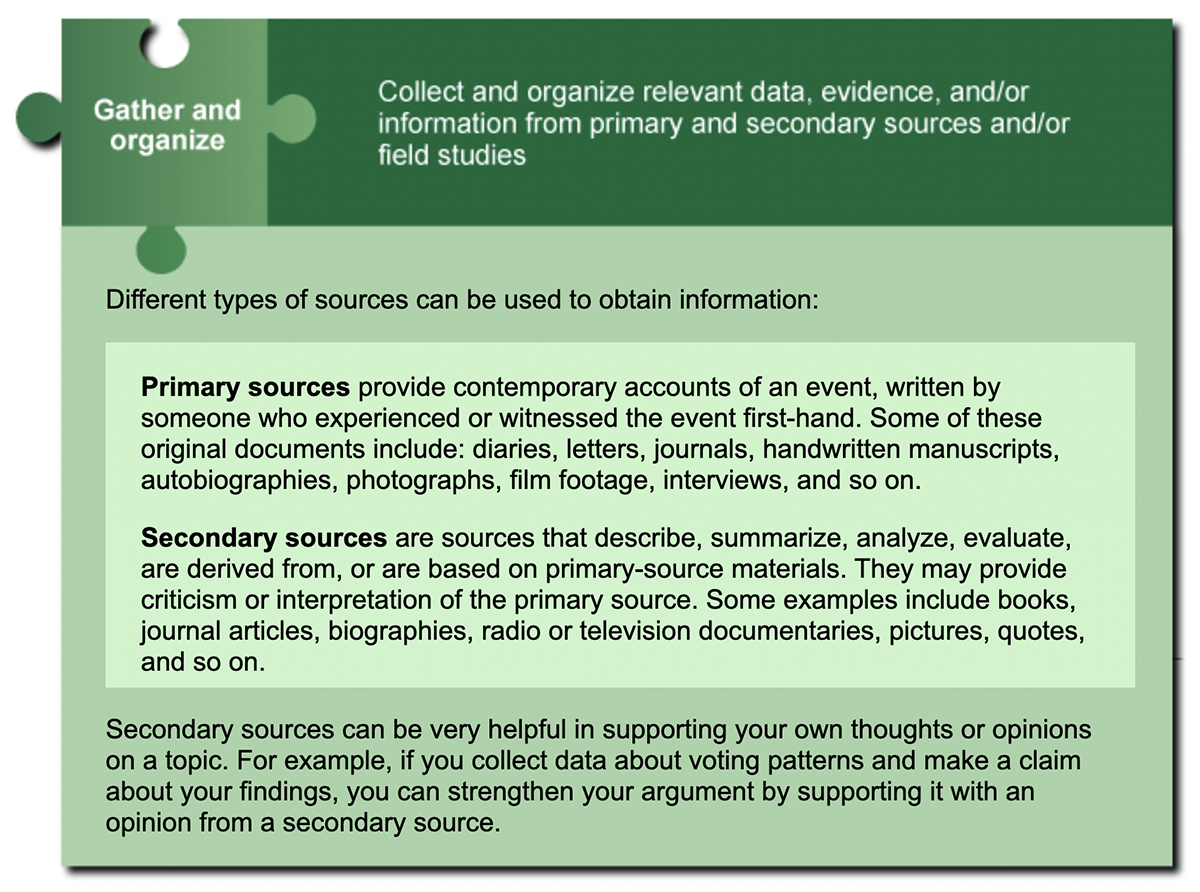

After you have formulated a good question, the next logical step in an inquiry is to gather and organize information in order to find evidence to answer your question.

Take a break!

Excellent work! You have just completed the section on choosing and creating an inquiry question. Now is a great time to take a break before you move on to the next section on research using primary sources.

Research using primary sources

Primary source research can involve collecting raw data on a specific topic directly from the source. In other words, the researcher obtains the original data from the source first-hand. Tools used to collect data from primary sources include surveys, interviews, and participant observations.

Press the following tabs to know more.

Research using secondary sources

When the information you’re working with is not first-hand information, it is called secondary research. It was collected and reported by another researcher and comes to you second-hand. You do secondary research by consulting resources such as books, journals, articles, or videos that have been developed by others. Based on what you find out, you can draw conclusions or develop plans for further research.

For example, if you’re interested in determining how a specific age group affects community participation, you could search for relevant information in articles found at libraries or online. By consulting secondary sources, you’re studying what others have done and learned, before setting out to collect your own data.

Try it!

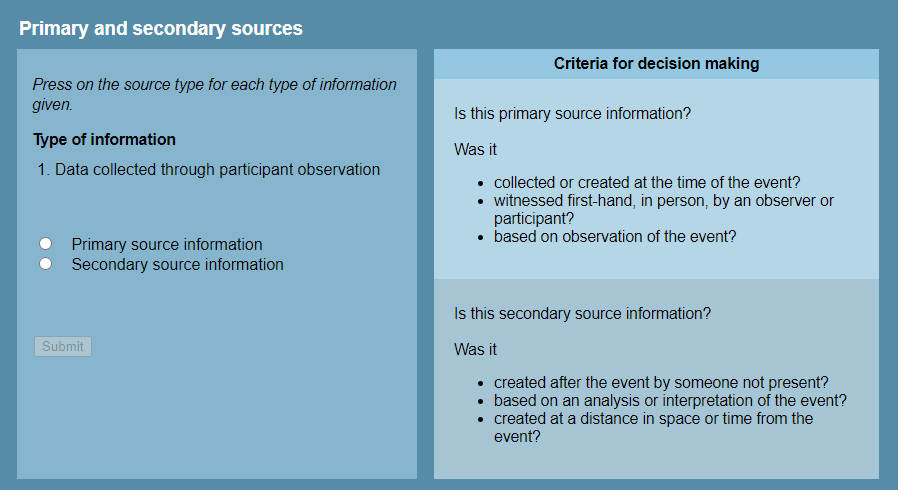

Using what you’ve just learned, access the following interactive entitled Primary and Secondary Sources to determine whether each of the following items would be considered a primary or a secondary source.

Press here for the accessible version of Primary and Secondary Sources. (Opens in a new window)

Press the Start button to access the following interactive. This interactive will open in a new window.

Start (Opens in a new window)

Start (Opens in a new window)

Searching for primary sources

Some primary source information, such as that found in original letters, diaries, or photos, is available in reference libraries or archives.

Searching for secondary sources

You’ll find plenty of secondary sources in databases, in online articles, and in libraries.

Press the following tabs to learn more about common places to search for secondary sources.

Checking sources

When you select secondary sources, you need to check that the information in them is valid and accurate.

Press the following tabs to learn more about the components of a source you need to assess.

Citing sources

For this course, whenever you formally cite (acknowledge) sources that are not your own, you need to cite them properly. There are three main styles including APA, MLA, or Chicago style. For this course, you will be following the Chicago style of citation.

Now that you have some background in how to gather information as part of your inquiry, now is your chance to give it a try.

Doing research using primary sources

Find three people in your community who are willing to participate in your research – in person, on the phone, or online.

Conduct a short interview with each of them by asking the question, "What do you think are the five most critical issues affecting the First Nations, Inuit, and Métis peoples today?"

Use a data collection sheet to record their responses. For example, you can access the graphic organizer entitled "Data collection sheet: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit studies inquiry (Opens in a new window)" to complete the activity.

Note that, because this information is being gathered first-hand from participants in the inquiry, it is considered primary source data. You’ll work with primary source data you collect, as you navigate the remaining steps in this inquiry.

- How does recording the information in a chart help you to understand it?

- Next time, how will you change your chart so that it is easier for you to work with?

The next step in the process is to interpret and analyze the findings.

Portfolio

Using a Venn diagram to compare information

Once you’ve gathered your information, you’ll organize it by completing a Venn diagram. Each circle will contain the interview responses from one of your subjects and afterwards, add your work to the print or digital folder that you are using for portfolio entries.

Access the following fillable and printable document Venn Diagram: First Nations, Métis, and Inuit Studies Inquiry (Opens in a new window) to complete the activity.

Record the similarities in the overlapping areas, and the differences in the non-overlapping areas. Once you have finished, answer the following questions underneath your diagram.

- When you’ve filled in your Venn diagram, examine the results.

- Which issues did your subjects identify as being the most critical?

- Did any of your subjects identify the same issues as being the most critical? If so, what do you think that indicates? If not, what do you think that indicates?

- How could you revise or rerun your inquiry to check your results?

- Did you get any insights into your subjects or the issues raised by conducting this basic research activity? What were they?

Now that you have a preliminary list of issues that are considered significant, you’ll come back to it from time to time as you work through the course. After analyzing your information, the next step is to evaluate what you’ve found and draw conclusions, based on sound judgement of the evidence. Examine the following image to learn more about it.

Moving from critical thinking to social action

What did the evidence tell you about the question being investigated, and which ideas have become clearer after your inquiry?

Think

Think about the following questions:

- Does the evidence support what you originally thought, or not?

- What conclusions can be drawn?

- How are your ideas about the issue changing?

- Is there anything new you’ve learned that you would change or add to your position?

Communicate

Once you have finalized your key findings, you need to think about what points to communicate.

Review the following image on information about how to communicate findings and create a plan of action.

The inquiry process has five basic components and these steps are interrelated. Using the process in this learning activity, you’ve documented the issues that are important in your community and/or globally.

Think

Think about the following questions:

- Do you feel strongly about any of these issues?

- Are you motivated to investigate them further, or become involved in creating solutions to them?

Portfolio

In a document of your choice, explore three challenges or issues First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities are facing that you know about and would like to learn more about, and potentially find ways to support. These might be ideas you’ll use in your culminating assignment.

Notebook

Take some time to consider the following questions and set your goals for the course in your notebook.

- What goals do you have for yourself in the course? Create at least three goals that you think can be completed by the end of the course.

- What skills are you hoping to develop or learn in the course (e.g. problem-solving, inquiry, etc.)? What skills are you confident in and which do you think you need to practice more often?

- How confident are you in your understandings of contemporary First Nations, Métis, and Inuit histories, perspectives, and issues? What are you hoping to learn more about?

- Do you feel confident in communicating your ideas? What are your strengths? What are your weaknesses when it comes to communicating your research, reflections, and ideas? How are you hoping to improve on these skills?

Moving into action

Action-based responses are a key focus in this course. The goal of the course is for you to not just learn about an issue or challenge in the world, but rather to also be a part of the solutions to these issues. Part of being an active citizen is that you search for ways to make the world better for current, as well as the future generations.

But before you make plans and commit to action, you must first have an understanding of the issue and know how you might best help the community you seek to assist. This comes from listening to members of the Indigenous community and their needs and act in a way that can assist them respectfully and reciprocally.

Notebook

Brainstorm some of the ways that you can start to approach social action and change, so that your actions are reciprocal and respectful to Indigenous communities.

As this course progresses, you’ll choose specific issues and then use your inquiry tools, knowledge, and skills to investigate them.

By the end of the course, you will have done the following:

- selected one issue that you believe to be significant and interesting

- researched the issue

- found out how you can support an Indigenous-led movement or initiative that aims to solve the issue

- created a proposal to support this movement or initiative in your school and/or community

As you progress, keep the culminating activity in mind. Think about how you can use the processes, skills, knowledge, and tools that you acquire during the learning activities to help you complete your final project.

Conclusion

In this learning activity, you have started your exploration of how you make relationships with the world around you and how your role as a critical thinker and a problem-solver can lead to positive changes in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit lives and communities. In the next learning activity, you will deepen your understandings of Indigenous relationships by learning more about respect, reciprocity and the connection to, and the significance of land and the natural world.

Journal

This is an opportunity for you to consider your progress. Think about the following questions, compose possible answers, and add them to the paper/digital file or folder that you created for all of your journal answers.

- What have you clearly understood in this learning activity? Please explain how you know or what you mean.

- What have you struggled with in this learning activity? Please explain how you know or what you mean.

- What remains unclear for you in this learning activity? Please explain how you know or what you mean.

- What will you do next to improve upon your understanding of this learning activity?

Self-check quiz

Check your understanding!

Complete the following self-check quiz to determine where you are in your learning and what areas you need to focus on.

This quiz is for feedback only, not part of your grade. You have unlimited attempts on this quiz. Take your time, do your best work, and reflect on any feedback provided.

Connecting to transferable skills

Ontario worked with other provinces in Canada to outline a set of competencies that are requirements to thrive. Ontario then developed its transferable skills framework as a set of skills for students to develop over time. These competencies are ones that are important to have in order to be successful in today’s world.

Read the following document entitled Transferable Skills Outline (Opens in a new window) to explore the framework and the descriptors for each skill. Download, print, or copy the information in the document into your notes - you'll refer to it in each unit.

Note the indicators that you think you will develop in this course. Throughout this course, you should revisit these skills to reflect on which ones you develop and if your original predictions were correct.

As you continue through this unit and the rest of the course, keep your notebook updated and be mindful of opportunities to apply and develop transferable skills.